St Mewan parish church

St Mewan parish church

Last Fall we joined the Cornish Family History Society, and subsequently corresponded with several other members who have been studying families with the same surnames to those of our ancestors. One couple invited us to call them when we arrived in Cornwall, and when we phoned they invited us to lunch and an afternoon drive.

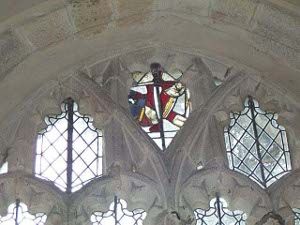

St Mewan parish church

St Mewan parish church

Hilary and John are retired French teachers who moved to Cornwall, near where Hilary grew up. They are interested in the new kind of history -- of families and localities and social developments. Living in St Austell, they are in the thick of the debates over preservation versus development. They are resigned to the building of a business park near their home, but vigorously protest the replacement of older buildings by modern boxes with utterly no redeeming architectural beauty.

After a delicious lunch of Cornish pasties, tea, and junket, we headed out for a tour of the surrounding country. We did not visit the most famous tourist destination in St. Austell, the Eden Project, which is an immense botanical garden under bubble-roofed geodesic domes sited in a former quarry. Instead we opted for a look at little villages with churches whose recorded history goes back seven or eight centuries, and some of which date back many centuries earlier.

The sky was overcast and the wind whipped over every open stretch of land, but whenever we entered a church it was still and peaceful. All but one of these old parish churches was open, but all the altarpieces were locked away. The church yards were full of moss-covered slate monuments, not to mention the memorials on the walls of the churches, inside and out, and occasionally on the floors. It would be quite an education just to understand each and every one of the local Saints for whom these churches (and their surrounding parishes) were named. St. Austell, for example, was a disciple of St. Mewan, who is known in France as St. Meen, while St. Ewe is one of the "Irish saints" who sailed to Cornwall to spread the gospel.

Stained glass in Creed church

Stained glass in Creed church

In Cornwall the buildings are mostly built of stone; this may be because all the wood was consumed in the mining industry, or perhaps because the local miners were adept at quarrying and cutting stone. The roofs are slate, and Hilary's cousin had a contract to reroof some of the local churches. So we learned that the slates are not uniform; at the peak of the roof they are smaller, gradually increasing in size towards the bottom. These stone buildings have an an air of agelessness, and the uniform grey-brown color makes all the villages look alike. We did see one thatched roof, on an old building called the Mansion House.

The roads are quaint and dangerous, with no shoulders, narrowed down by the ancient hedgerows. It would be impossible to travel these roads on foot. The experienced local drivers all drive slowly and know the wide spots to wait for the other driver to pass; those in a hurry from out of town are frequently in smash ups. Of course widening the country roads in the interest of vehicle safety would destroy the hedgerows which typify the Cornish countryside.

The farms and villages are tucked away between the hills to avoid the wind, John says. They are seldom more than a couple miles apart, and range from a few old cottages to a few hundred. We saw parish churches and Methodist chapels, erected during the surge of Methodist fervor that John Wesley brought to the Cornish miners. Church attendance is down now; many of the Methodist chapels are now homes or businesses, and many of the Anglican churches share a rector and have communion on alternate weeks. Sometimes, as in St Mewan, there will be a church where there isn't even much of a village; it was once a popular place for marriages, and people would come to this church from nearby towns to be wed. Two towns, Creed and Grampound, shared a church. Grampound residents were expected to attend services in Creed, a long and steep climb, especially on a cold and windy day. For funerals of Grampounders, a  Thatch-roofed Mansion House

wheeled bier carried the casket uphill to the Creed church -- it is still in place at the rear of the church.

Thatch-roofed Mansion House

wheeled bier carried the casket uphill to the Creed church -- it is still in place at the rear of the church.

Each church has its tower. Most of the ones we saw were square and sturdy, like miniature castles. Only one, St Ewe, had a spire, a conical affair built around 1350. Inside, granite arches divide the various seating sections (gentry closest to the pulpit, servants in back, sometimes around the corner, according to an old seating chart posted on the wall). Wooden carvings at the ends of choir stalls and on the pulpits and stone sculptures near the ceilings were lively additions. In one church we found an old set of stocks, kept in the church to safeguard it. In some cases we found fragments of ancient stained glass windows, but most windows are now clear glass -- a good thing for us, on a dark afternoon, to have as much light as possible. Just about every church has its set of bells. We could see the bell ropes hanging in readiness for Sunday morning. The chosen bell-ringers grasp the plush-covered ropes to ring the changes; the more important the parish, the more bells.

Although most of the churches are relatively modest in size and decoration, we found one -- St. Michael of Caerhays, which is the church of the Trevanion family -- where the family has installed memorials of various kinds: a life-sized statue of a captain in the Royal Navy from 1785-1808, a marble plaque with poem in memory of several family members, and a corner monument in honor of William Trevanion who was born in 1727.

Our road took us through a half-dozen little villages, most of them consisting only of a High Street, or Fore Street, or Market Street. There is usually a pub and a couple of small shops. Surrounding each of the villages, two hundred years ago, were tin or copper mines, some of them small adventures, some of them the work of larger companies. We drove to the coast, to see a sheltered sandy beach where the Atlantic ocean tides play. In Hewas Water, where there was once a large mine, an ancestor, Josiah John Johns, once owned the blacksmith shop and ran the local pub, the Plough -- no trace of  Did William Rowe live here?

either remains, although Hewas Water itself is still a recognizable settlement.

Did William Rowe live here?

either remains, although Hewas Water itself is still a recognizable settlement.

One of our last pauses was at Pothole, where great-great grandfather William Rowe lived in 1841. Today it is an unknown and virtually unmarked place, with perhaps a half-dozen buildings, which were certainly built in the nineteenth century and possibly as long ago as 1841. Today the landholder has put up a fishing centre, with a lot to park about 20 cars.

Returning to St. Austell, we climbed the hill north of town to see several homes and business locations of Hilary's ancestors. The school she attended as a girl has been replaced by a modern building, but the old school is still standing, the work of a local architect. Hilary thinks it will cost too much to save the school, and the building would not get much use as a community center, but the destruction is suspended while the debate goes on.

Clay mining is down, too. The mines are owned by a French-run multinational, which has gradually shut down the less profitable pits. South American sources of china clay are more economical to operate. An old lumberyard is the site of a new housing development: more than a hundred houses will be built, including, it is promised, affordable low-cost housing.

We know that in 1865 our ancestors left a pitiful existence as Cornish miners, and within twenty years became prosperous midwestern American farmers, landowners and pillars of the community. Had they remained in Cornwall they would have remained impoverished and out of work. In 2003, Cornwall is still the poorest county in England, the only county depressed enough to qualify for European Union economic aid. Now that modern technology has created knowledge industries that don't depend upon local natural resources, but just on human brainpower, we hope that regions like Cornwall can soon prosper again.

It was getting colder, and it was starting to rain, so we gratefully accepted John's offer of a ride to the train station. The train was an hour late, which didn't seem to surprise any of the other people in the waiting room. The passengers who missed their connection in Truro were taken by bus to Falmouth, and we indulged in a taxi ride back to Pentina Cottage, sharing the cab with an experienced British road warrior.