Paris Opera Garnier

Paris Opera Garnier

We left our apartment on Rue Victor Masse and descended the hill to the parish Church of Notre Dame de Lorette. One can easily tour one beautiful church each day, and just by altering our path a couple of blocks we can always find another church to see. After admiring the architecture inside and out we descended the front steps and caught sight of the gold top of the old Paris Opera Garnier.

Paris Opera Garnier

Paris Opera Garnier

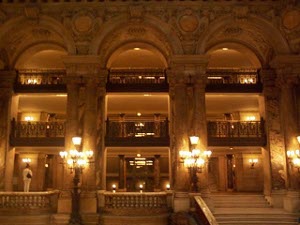

The Opera house was indeed beautiful inside, built during the reign of Napoleon III. Today it has been elbowed out of the artistic spolight by the newer Opera House at the Bastille; this was the plan of the French government to have an opera house that would be accessible to the masses. It might be the case that the masses still prefer rock concerts to opera, but if so, that data has not been published by the French government!

The old building is lavish, opulent, with statuary and dramatic marble staircases and elegant plush boxes, and is still being used for some performances -- concerts and ballets -- but we did not find a performance we wanted to attend. We wandered around the inside -- part of the old Opera House is now a museum -- explored the box seats, the cloakrooms, lounges, and the ceiling painted by Marc Chagall. We imagined the scene in the nineteenth century, with aristocrats dressed in finery, sitting in their personal boxes to watch performances. A special exhibit from Spain showed a variety of modern costumes for classical operas; we wished we could see them all in action.

The Catacombs are in the southern part of Paris, the 14th Arondissement, reached by RER trains. We paid our money, descended far underground, and began to walk. After descending many stairs we walked underground for quite a while. It wasn't a long straight passage, but twisted and turned -- although the map showed it generally following a straight direction. The guide book had said we would wonder if we would ever reach the catacombs, and we did. There were few signs, few lights, giving an intended eerie glow to the surroundings.

Inside the opera house

Inside the opera house

Then a sign told us to respect the dead, and we did, as we soon found ourself snaking around through uncountable corridors lined with bones and skulls, stacked and packed neatly several feet high. The ceilings were low and the light remained dim. As a tourist display it was amateurish; as a sacred resting place it was inadequately protected and guarded.

In the nineteenth century, many Parisian cemeteries became public health problems, due to inadequate burial practices. In addition, there was no more room for additional graves. All the cemeteries were nominally Catholic, as France was and is nominally Catholic. So the Church came up with a plan to exhume all the bodies from several Parisian cemeteries in their entirety, to consecrate huge underground catacombs, twenty meters underground, and then move the bones of an estimated three million people to these caves. It was a monumental undertaking and took years to accomplish. One could see that those who stacked the bones and skulls underground had some artistic leanings, and so the skulls sometimes formed patterns and designs on the faces of the piles.

We were all awed by the sight, especially Dan. There were signs that some bones and skulls had been stolen by visitors in the past. We don't know if the Catacombs were immediately made into a tourist venue, or if not, when that practice started. Every hundred feet there would be a small shrine or memorial plaque, generally naming the cemetery from which the bones in that particular area had been taken, but we found it hard to believe that there had been any order in the whole business. As genealogists who have made a practice of photographing our relatives' graves, we were glad we didn't have to deal with relatives who had been buried in these Parisian cemeteries.

Just as we had wondered when the long approach corridor would end and we would find the catacombs, we wondered when the long path through the catacombs would end and we could return to the surface. The exit corridor was shorter, and we slowly mounted the stairs back to the surface, exiting several blocks away from the entrance stair. The fresh air and sunlight was welcome, the exit door wonderfully anonymous.

There are several cemeteries in Paris where famous persons are buried. These cemeteries -- Pere Lachaise, Montparnasse, Montmartre -- were not  Polished skulls

emptied out into the catacombs. They are also tourist attractions, and visitors are given guide maps to find the graves of well-known dead people to see. When we returned from the Catacombs to Montmartre we found a subway station near the cemetery there, and looked around briefly. The burial practices are somewhat different from most of the U.S., with large stone vaults or at least stone slabs surrounding a flat gravestone. Often one sees a large marker naming the deceased person(s) and then resting on top, small engraved polished stones expressing the thoughts of the family members who are / were still alive.

Polished skulls

emptied out into the catacombs. They are also tourist attractions, and visitors are given guide maps to find the graves of well-known dead people to see. When we returned from the Catacombs to Montmartre we found a subway station near the cemetery there, and looked around briefly. The burial practices are somewhat different from most of the U.S., with large stone vaults or at least stone slabs surrounding a flat gravestone. Often one sees a large marker naming the deceased person(s) and then resting on top, small engraved polished stones expressing the thoughts of the family members who are / were still alive.

We saw some signs that this cemetery was still active, but apparently only in case there was space in a family plot for additional graves. And there were certainly many tombs of the rich and famous - dukes and duchesses, counts and countesses, commanders of the legion of honor, generals, writers, artists, scientists . . . Today we noted the graves of the writer Stendhal and the physicist Ampere.

In the U.S. there has been plenty of space in cemeteries and memorial parks, so one finds plenty of grass and trees and shrubs, piles of flowers on the graves. In the Montmartre Cemetery the graves are closely spaced, separated by stone or gravel paths, or narrow paved roads to let a hearse move through. Many of the families have died out or moved away from Paris (or lost interest in tending their ancestors' graves) so a lot of the vaults are cracked, the iron rusted, sculpture broken or deteriorated. This is no different than the weathering of gravestones in any cemetery, though. Those who have visited New Orleans cemeteries will find many similarities in design and layout.

What does it say about Paris to know that its catacombs and cemeteries are tourist attractions? Perhaps a greater ease in dealing with death than in other societies, perhaps a great respect for a romantic and turbulent history, perhaps something we haven't tumbled to . . .