Since we met at Oberlin College, we had to visit Oberlin, Kansas. It's a tiny town with a big museum, consisting of 13 old buildings, donated and moved downtown. We learned that the town was originally named Westfield, until a pioneer from Oberlin, Ohio offered a tract of land to the city if the name were changed.

The museum is a multi-roomed affair, crammed full of donations from practically everybody. We began our visit by watching a video of the Last Indian Raid. After the Sioux Wars of 1876, some Northern Cheyennes were forced from their South Dakota homeland to an Oklahoma reservation. Having received little of the food, clothing and shelter they had been promised, they escaped in 1879 and headed toward South Dakota. Chased by the Army, the Indians raided the homes and ranches of settlers, getting fresh supplies and killing the new homesteaders, some of whom were fresh from Europe, ignorant  Downtown Oberlin

and innocent of the history of oppression. Oberlin was especially hard hit. The Cheyenne made it into Nebraska, but the remnants were rounded up and returned to Oklahoma. The Cheyenne escaped again and most were then massacred. From all points of view a sad story.

Downtown Oberlin

and innocent of the history of oppression. Oberlin was especially hard hit. The Cheyenne made it into Nebraska, but the remnants were rounded up and returned to Oklahoma. The Cheyenne escaped again and most were then massacred. From all points of view a sad story.

The museum was primarily a description of life in Oberlin starting around the turn of the twentieth century. Sheet music, clothing, military uniforms, toys, a deadly-looking dentist's office, farm tools, gas station, school house, general store, doctor's office, railroad station, and a replica of a soddie or sod house made by the townspeople. This soddie had a wood floor, probably to survive the summer visitors better than a dirt one. Old newspapers had been carefully cut out to make lacy-looking curtains and shelf paper. One thing that appealed to us about the Oberlin Museum is that there was nothing pretentious -- just a collection of old objects from the surrounding farmsteads and town houses which, put together in a fairly large, thirteen-building scale, make an impressive display.

We drove around the deserted town trying to find lunch. The East-West road had a couple of places that had closed, a Pizza Hut, and the convenience store behind the gas station. We went back through town and discovered that the old bank building had been turned into a hotel and restaurant. The Tellers' Room was a kind of freshly redecorated Victorian expresso bar in downtown Oberlin. Being flexible, we adjusted our attitude and decided to try lunch. We were the only customers.

"We have Santa Fe Chicken, French Onion Soup, and Barbecued Pork," said the young waittress, who was learning how to serve tables in a Fine Dining establishment. Elsa ordered the chicken, Bob the soup and Pork. "Do you mean you want both?" asked the waittress. It turned out the Soup was intended as a meal in itself, but being Kansans they adjusted and produced a cup of soup in advance of the luncheon dish.

All the food was very good, and the atmosphere quite nice. We don't know if there are enough Kansans who will drive in to town for a fancy dinner to let the owners make a profit, but we wish them the best. The chef certainly likes to cook, and the sauces were especially flavorful. The fruit salad accompaniment came out of a can, but was still the right accent flavor. The background music was New Age instrumental versions of hymns. They had some nice displays of old bank paraphernalia. We would recommend a luncheon here.

We spent two nights in Garden City, Kansas, and were somewhat astounded by the energy, enthusiasm, and achievements of its citizens. We learned the  Stevens House, Garden City

following from (a) taking the walking and driving tours and (b) going to the free county museum: Garden City used to have a factory producing a considerable amount of beet sugar. Garden City was for a while the home of Buffalo Jones (see below). Garden City's irrigated farms produce enormous amounts of feed grains. Rather than ship those grains elsewhere, Garden City is the home of some of the world's largest feedlots as well as the world's largest beef packing plant. (Our noses had originally detected the feedlots as we drove into town.) The modern IBP plant (for Iowa Beef Producers) has recently been sold to Tyson Foods, the megameat company. The plant ships "boxed beef products" containing vacuum sealed plastic packages of beef ready for labelling and immediate sale in the supermarkets. In otherwords, it is a combination slaughterhouse and retail supplier. Garden City contains the world's largest free municipal concrete swimming pool, which requires sixteen lifeguards (when it's open). And finally, Garden City is the place were millions of humorous post cards featuring giant rabbits, grasshoppers, and the like, were produced in the 1930s by Frank D. "Pop" Connard in his photography studio using etching tools.

Stevens House, Garden City

following from (a) taking the walking and driving tours and (b) going to the free county museum: Garden City used to have a factory producing a considerable amount of beet sugar. Garden City was for a while the home of Buffalo Jones (see below). Garden City's irrigated farms produce enormous amounts of feed grains. Rather than ship those grains elsewhere, Garden City is the home of some of the world's largest feedlots as well as the world's largest beef packing plant. (Our noses had originally detected the feedlots as we drove into town.) The modern IBP plant (for Iowa Beef Producers) has recently been sold to Tyson Foods, the megameat company. The plant ships "boxed beef products" containing vacuum sealed plastic packages of beef ready for labelling and immediate sale in the supermarkets. In otherwords, it is a combination slaughterhouse and retail supplier. Garden City contains the world's largest free municipal concrete swimming pool, which requires sixteen lifeguards (when it's open). And finally, Garden City is the place were millions of humorous post cards featuring giant rabbits, grasshoppers, and the like, were produced in the 1930s by Frank D. "Pop" Connard in his photography studio using etching tools.

he pride of Garden City's citizens is evident. "We work at it," advised the lady in the museum when we complimented her on the exhibits. The museum, it should be pointed out is right next to the zoo, which is free to pedestrians, although a fee is charged for vehicles to drive through and view the animals. We did not tour the zoo, so all we can tell you about for sure is camels and probably elephants. For quite a few years the elephants used to play in the swimming pool at the end of the season, but the laws requiring careful control of zoo animals in the State of Kansas put an end to that practice. Yet the county has undergone many changes, as witness the exhibit of photos of twenty or thirty ghost towns in the museum. Perhaps the biggest risk to Garden City (and the surrounding thousands of square miles) is the potential depletion of the aquifer which is used to irrigate the farms. If the water dries up (so to speak) the grain production will plummet, taking with it the economic advantages for beef production. But the enthusiasm and capital of Garden City's citizens may surmount that hurdle, too.

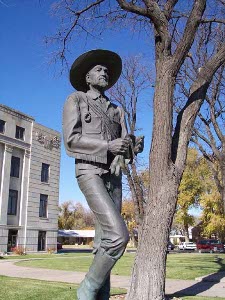

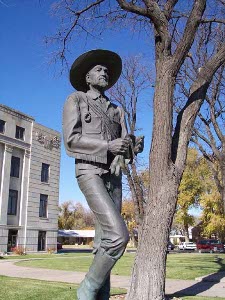

We had never heard of Mr. C. J. "Buffalo" Jones. His statue in front of the courthouse shows a slender, handsome westerner, and it took six panels of closely written type around the base to tell his story. Here it is:

CHARLES JESSE "BUFFALO" JONES,

Immortalized by author Zane Grey in his book, "The Last of the Plainsmen," is listed in the National Archives as one of the preservers of the American bison, and his colorful, many-faceted career spanned several continents.

Born January 31, 1844, in Illinois, Jones became fascinated as a youth with the capture of wild animals. He came to Kansas in 1866, where he developed into a skilled plainsman. With his knowledge and love of outdoor life, he made a good living for his wife, two sons and two daughters, hunting buffalo and capturing wild horses.

On April 6, 1879, Jones, together with John Stevens, W. D. and James F. Fulton, founded Garden City. Each man homesteaded 160 acres. The Jones addition lies west of Eighth Street. The southeast corner of Jones Quarter is approximately one block south.

Jones persuaded the Santa Fe Railroad to stop the train here and Garden City grew and developed. Jones was elected the town's first Mayor, and also became the area's first Representative in the Kansas Legislature. He successfully promoted Garden City as the County seat. He donated this land for our courthouse and built the first courthouse here.

C. J. "Buffalo" Jones

He built the "Buffalo" Jones block southeast of here on Grant Street, the Herald Building and the Lincoln and Grant buildings on 6th Street. His home at 615 N. 9th St. still is used as a dwelling.

Jones helped develop and build an irrigation ditch which ran 100 miles from the Arkansas River through Kearny and Finney counties irrigating some 75,000 acres. He constantly boosted Garden City and western Kansas.

Fearing the extinction of the buffalo, Jones made numerous adventure-filled treks into the Oklahoma and Texas Panhandles where he captured 57 buffalo calves, returning them to his ranch here. Offspring from the basic herd spread throughout the world thereby saving this race of noble prairie animals. The buffalo in the herd on the game preserve just south of Garden City are descendants of those calves.

In 1898, Jones used two horses to make the run for land into the Oklahoma Cherokee strip.

In 1897-98, Jones journeyed to the Arctic Circle. Undergoing terrible hardships, he succeeded in capturing five baby musk oxen only to have them slaughtered by superstitious Indians.

In 1901 he was appointed by his friend, Theodore Roosevelt, as the first game warden of Yellowstone National Park.

In 1906, he developed a ranch and game preserve on the north rim of the Grand Canyon. There he continued to crossbreed cattle and buffalo to produce cattalo, an experiment he had started with his herd near Garden City. Zane Grey visited the ranch, and his book, "Roping Lions in the Grand Canyon," tells of their adventures. Grey, a little known dentist from New York, became enchanted by Jones and the west. He went on to become a great western story writer. By his own admission, Grey based the character of his heroes on some facet of the character of Buffalo Jones.

Other books about Jones are "Lord of Beasts," by Easton and Brooks, "Forty Years of Adventure on the Plains," by Colonel Inman, and "Buffalo Jones" written by Ralph Kersey, a local pioneer.

Jones' safari to Africa, in 1909, where he lassoed, captured and photographed all types of wild animals, was much publicized and brought him wide acclaim and recognition. The book, "Roping Lions in Africa", by Guy H. Scull, recounts this adventurous undertaking. On his return from Africa he embarked on a lecture tour inspiring large audiences with views of his work in the animal kingdom.

In 1914, he returned to Africa where he lassoed, but failed to capture, a vicious gorilla, one of the few animals he missed on his first trip. Here he contracted malaria, from which he never fully recovered.

Colonel Jones, as he was called by his peers, was awarded a Medal by Edward VII, King of England, for his work with animals.

His many exciting ventures were further recognized by election to the Cowboy Hall of Fame in 1959.

Charles Jesse Jones died October 15 1919 in Topeka. He is buried here in Valley View Cemetery beside his wife Martha Walton Jones, and their two sons.

Jones was an undying friend of Garden City and Southwest Kansas and this memorial is in recognition of his service to our city, state and nation. His character, courage and indomitable spirit make him truly one of our finest citizens and an example for all who follow.

Dedicated July 4, 1979,

Buffalo Jones Memorial Committee,

Finney County Historical Society,

Helen Harp, Chairman.

C. J. "Buffalo" Jones

He built the "Buffalo" Jones block southeast of here on Grant Street, the Herald Building and the Lincoln and Grant buildings on 6th Street. His home at 615 N. 9th St. still is used as a dwelling.

Jones helped develop and build an irrigation ditch which ran 100 miles from the Arkansas River through Kearny and Finney counties irrigating some 75,000 acres. He constantly boosted Garden City and western Kansas.

Fearing the extinction of the buffalo, Jones made numerous adventure-filled treks into the Oklahoma and Texas Panhandles where he captured 57 buffalo calves, returning them to his ranch here. Offspring from the basic herd spread throughout the world thereby saving this race of noble prairie animals. The buffalo in the herd on the game preserve just south of Garden City are descendants of those calves.

In 1898, Jones used two horses to make the run for land into the Oklahoma Cherokee strip.

In 1897-98, Jones journeyed to the Arctic Circle. Undergoing terrible hardships, he succeeded in capturing five baby musk oxen only to have them slaughtered by superstitious Indians.

In 1901 he was appointed by his friend, Theodore Roosevelt, as the first game warden of Yellowstone National Park.

In 1906, he developed a ranch and game preserve on the north rim of the Grand Canyon. There he continued to crossbreed cattle and buffalo to produce cattalo, an experiment he had started with his herd near Garden City. Zane Grey visited the ranch, and his book, "Roping Lions in the Grand Canyon," tells of their adventures. Grey, a little known dentist from New York, became enchanted by Jones and the west. He went on to become a great western story writer. By his own admission, Grey based the character of his heroes on some facet of the character of Buffalo Jones.

Other books about Jones are "Lord of Beasts," by Easton and Brooks, "Forty Years of Adventure on the Plains," by Colonel Inman, and "Buffalo Jones" written by Ralph Kersey, a local pioneer.

Jones' safari to Africa, in 1909, where he lassoed, captured and photographed all types of wild animals, was much publicized and brought him wide acclaim and recognition. The book, "Roping Lions in Africa", by Guy H. Scull, recounts this adventurous undertaking. On his return from Africa he embarked on a lecture tour inspiring large audiences with views of his work in the animal kingdom.

In 1914, he returned to Africa where he lassoed, but failed to capture, a vicious gorilla, one of the few animals he missed on his first trip. Here he contracted malaria, from which he never fully recovered.

Colonel Jones, as he was called by his peers, was awarded a Medal by Edward VII, King of England, for his work with animals.

His many exciting ventures were further recognized by election to the Cowboy Hall of Fame in 1959.

Charles Jesse Jones died October 15 1919 in Topeka. He is buried here in Valley View Cemetery beside his wife Martha Walton Jones, and their two sons.

Jones was an undying friend of Garden City and Southwest Kansas and this memorial is in recognition of his service to our city, state and nation. His character, courage and indomitable spirit make him truly one of our finest citizens and an example for all who follow.

Dedicated July 4, 1979,

Buffalo Jones Memorial Committee,

Finney County Historical Society,

Helen Harp, Chairman.

Downtown Oberlin

and innocent of the history of oppression. Oberlin was especially hard hit. The Cheyenne made it into Nebraska, but the remnants were rounded up and returned to Oklahoma. The Cheyenne escaped again and most were then massacred. From all points of view a sad story.

Downtown Oberlin

and innocent of the history of oppression. Oberlin was especially hard hit. The Cheyenne made it into Nebraska, but the remnants were rounded up and returned to Oklahoma. The Cheyenne escaped again and most were then massacred. From all points of view a sad story.

Stevens House, Garden City

Stevens House, Garden City C. J. "Buffalo" Jones

C. J. "Buffalo" Jones