The Three Graces

The Three Graces

We agree that our two-week visit to Liverpool was one of the most satisfying parts of the Summer. Like many of the cities we've seen, Liverpool is filled with energy, creating new buildings while preserving her historic past -- both the good and the bad. Liverpool is fortunate to be surrounded by exceptionally interesting towns and landmarks. In this report we separate the city itself from the places we reached by train.

The Three Graces

The Three Graces

Visiting Liverpool, we stayed in a lovely, bright and spacious apartment across the Mersey River in Birkenhead. It was just about ideal for us, because we were away from the noise and bustle of the city but could enjoy its dramatic skyline and watch boats of many kinds move up and down the river. We could catch the train just a ten-minute walk away and be deposited in the center of Liverpool. To begin, we bought a "rover" ticket which let us ride quite a few trains, buses, and even the ferry for a smallish fare.

Next, we went to the nearly new Museum of Liverpool, on the waterfront next to the three graces (which are three lovely waterfront buildings). While Liverpool is an old word meaning something like "pool of brackish water," The Royal Liver Building was the flagship headquarters of the Royal Liver Assurance Society, which was founded, so they say, in the Lyver Inn (so the name "Liver" is pronounced with a long "i") and has the enormous green statues of an unknown bird (probably cormorant) with something in its mouth (not a frog). This emblem appears all over the city, looking vaguely fantastic.

Lion, an Early Locomotive

Lion, an Early Locomotive

We were very moved by some of the exhibits in the museum. The first hall explained how Liverpool was a huge port city for hundreds of years, and became synonymous with transatlantic passages for many future Americans. Before the days of airplanes and containerships, there was always work to be found on the waterfront, so much so that an elevated train travelled from one end of the piers to the other, carrying working men to and from their jobs.

Now that the port business vanished, it's not surprising that modern Liverpool has high unemployment and high poverty. We saw movies and heard tapes of Liverpudlians talking "Scouse," (rhymes with Mouse) a regional dialect named for a popular seamen's stew of the same name (which we tried for lunch in the museum cafe -- you can Google scouse for recipes).

At the height of the Liverpool shipping boom, Liverpool was connected by sea with all the nations of the world, but particularly those of the British Empire, and accordingly we saw an amazing (for England) and moving documentary, 20 minutes long, called "The Power and the Glory?" which called to mind the violence exercised over the years in building that Empire.

Rooftop Space, Liverpool Library

Rooftop Space, Liverpool Library

A huge number of Irish refugees landed in Liverpool during the potato famine. Most went on to emigrate on the Liverpool sailing ships to the U.S. and Canada, but many stayed on and worked in Liverpool. The museum pays careful attention to the various neighborhoods and regions which make up the greater Liverpool area. Many visitors take time to view places where they have grown up or live now. The city was badly damaged by German bombing in 1940 but many neighborhoods were rebuilt. Still, according to the museum this city continues to struggle; expected life span is less than elsewhere in the U.K. while unemployment continues to be high.

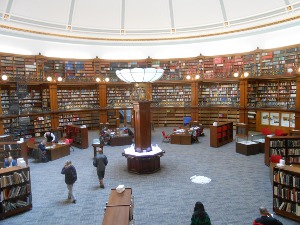

One pleasant sign is the large number of families with small children visiting the museum. As in other English cities, many municipal museums are free, so children can pay repeat visits and find their favorite spots. Having seen some art and history museums, we wanted to see the library. We've seen some gorgeous libraries this summer, but here we saw the best one yet.

The Central Library in Liverpool was first opened in 1857 as the William Brown Library and Museum and contained some handsome rooms, like the circular Picton Reading Room. In the devastating Blitz of 1940 the library was nearly flattened but eventually reopened, and an extension was created. By 2003 the city decided it was time once again to rebuild and remodel. After ten years of planning and three years of construction, it is once again open. The modern version, designed by Austin-Smith:Lord, is breathtakingly beautiful.

Picton Reading Room

Picton Reading Room

We happily wandered the floors, from the roof gallery at the top to the fiction and cafe on the ground floor, pausing to step through side doors into the carefully preserved parts of the old library. Besides the Picton Room we saw the Hornby Library and the Oak Room, with an elephant folio of Audubon's Birds of America.

We visited the Liverpool Cathedral, a 74-year project that was formally opened by the Queen in 1978. It is the largest Anglican Cathedral in Britain. The most moving memorial in the cathedral was the tribute to the son of the bishop who started the construction work. Captain Noel Chavasse is the only person ever to have been awarded two Victoria Crosses. A physician, he served as Medical Officer to the Liverpool Scottish regiment, and received both his medals for going out into no-man's land to rescue wounded, first on the Somme, and then near a captured German blockhouse, during which action he was killed when a shell landed near him and exploded.

The Liverpool Cathedral was conceived, funded and construction begun at a time when Liverpool was at the height of its glory as the transatlantic shipping capitol of Great Britain. To us it seemed overpoweringly large, and we found ourselves thinking that quite a small church, like some we saw in Eastern Slovakia or rural America, was sufficient for the religious needs of the congregation, while a huge church seems to be primarily a symbol of power.

Dwarfed by the Cathedral

Dwarfed by the Cathedral

As if in recognition of this, the many churchmen and volunteers we met inside the cathedral were focused on a highly personal level of ministry and evangelism. A visiting choral group was giving a concert in one part of the nave. There was even a neon sign within the cathedral, "I felt You and I know You loved me," which served to bring the enormous scale of this cathedral down to human size.

Right across the street from the cathedral is Chinatown, with a really fine entrance arch over Nelson Street. We found a mom-and-daughter Cantonese-style Chinese restaurant and enjoyed a delicious luncheon.

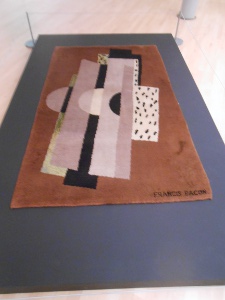

Unlike the Walker Gallery, Tate Liverpool had plenty of space for the exhibits and generally good lighting. It is a branch of the Tate in London, understandably located here since Mr. Tate hailed from Liverpool. It's modern art, meaning works created post 1900.

We found quite a bit we liked, and -- as always in a museum of modern and (especially) contemporary art, quite a bit we didn't like. Moreover, some of us liked what others of us didn't, and vice versa. Still, on the whole, we both liked the Tate Liverpool very much (although Bob's favorite of the last two days was a sculpture in the Walker Gallery.)

Rug by Francis Bacon

Rug by Francis Bacon

In the nineteenth century and part of the twentieth century, Liverpool was a major maritime port. With the current decline of shipbuilding and transport, the city is working hard to develop tourism as a major industry. One result is that old historic buildings (for example, Albert Dock) are re-purposed into museums, and new museums (e.g., the Central Library and the Museum of Liverpool) are being developed. Apparently this change of emphasis is working, as we noted when we watched crowds of both cruise boat passengers and conventioneers thronging the pavements in the Culture Quarter.

The Merseyside Maritime Museum and the International Slavery Museum are co-located at Albert Dock, which makes for an intense visiting experience. Liverpool was the major port for the transatlantic trade for a long while, and many men from Liverpool were merchant mariners. The terrible losses to the merchant marine during the Battle of the Atlantic, followed by the loss of transatlantic passenger ship bookings to the airlines, and then the relocation of the port to Southampton, spelled misery after misery for these men and their families. (There were women, too, but at the time the merchant marine consisted mostly of men.) The loss of the Titanic, the Empress of Ireland, and the Lusitania, all ships homeported in Liverpool, was a terrible shock to this port and its people.

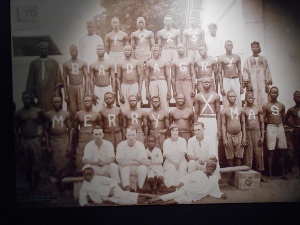

A Slaver's Christmas card

Liverpool was also the home port of many of the transatlantic slavers, and the International Slavery Museum, located within the Maritime Museum for obvious reasons, addresses that ugly history. After the transport of slaves was declared illegal in Britain, slave ships were condemned and their "cargo" brought to St. Helena, a tiny island in the South Atlantic Ocean. Recent archaeological excavations have revealed that many of the slaves died and were buried in mass graves.

A Slaver's Christmas card

Liverpool was also the home port of many of the transatlantic slavers, and the International Slavery Museum, located within the Maritime Museum for obvious reasons, addresses that ugly history. After the transport of slaves was declared illegal in Britain, slave ships were condemned and their "cargo" brought to St. Helena, a tiny island in the South Atlantic Ocean. Recent archaeological excavations have revealed that many of the slaves died and were buried in mass graves.

The museum does not shrink from illustrating examples of Liverpool's connection to the slave trade (in the Xmas card illustrated, the young White couple are Liverpudlians, the street signs are names of slavers).The extent of slavery at the current time is also covered. Both museums are sobering reminders of inhumanity.

We've gone sightseeing in and around Liverpool for ten days and haven't spent a day checking out Birkenhead, where we are staying.

It's on the other (southwest) side of the Mersey, but well connected with Liverpool by both train and vehicle tunnels. And it has a huge shopping center, about five or six blocks in one direction by two or three blocks in the other direction, with pedestrianized streets, indoor and outdoor markets and shopping centers and hundreds of stores.

We made a little map and set forth on foot, carrying a bag of already-read books to donate to the Salvation Army. We even had the address of the Salvation Army store, on the far side of the shopping center, so of course we walked through all the markets.

English schools are set to start again, we think next week. We believe the students only get the month of August off from school. Anyhow, a new year at school means new school uniforms for all the kiddies. We had seen something like this a couple of days ago and not recognized it for what it was. The store is a "regular" uniform store which handles all kinds of specialized work clothes for a variety of fields, all around the year, except for the end of August, when everything else is suspended to make way for back-to-school clothes. The store is full of racks and racks of school uniforms, and and the parents and children wait outside, the long queue stretching down past the next store!

Back to School Shopping

Back to School Shopping

On the way back we located the old priory, not far from our apartment, and right next door to the huge Cannell and Laird shipyard, which is working on a good-sized Royal Navy vessel. The priory dates from the 12th century, but of course the forced closure and looting of all the monasteries by Henry VIII deprived the English of a great deal of beautiful church buildings and treasures which, like this one, were allowed to fall into ruin. (That's not quite the way it is described on the sign boards, however!)

The priory was a profitable one, because the monks got a charter from the king allowing them to operate the Mersey ferry service (which, in fact, they had started doing long before the king issued the charter.) It has been declared a listed building, and now is slowly being restored (although most of the restoration is to a relatively recent building, as the twelfth century buildings provide at most foundation stones.

New Brighton Seashore

New Brighton was built up around 1840 expecting to be a posh seaside resort; but it was easily accessible to all the multitudes who found factory work near Liverpool so instead it became a crowded workingman's seaside resort.

Lifesavers Practice

Lifesavers Practice

Today the huge crowds are just memories, as savvy Brits head far south when they want to go to the beach - to places like Majorca and Cyprus, because the rule is that beaches around Great Britain and Ireland are often windy, and when they are windy they also have a pretty low wind chill factor.

Such as today - yellow wind alert. We had a chance to zip up the hoods on our jackets, which proved quite comfy, but even so we could not endure the full hike around the seafront in New Brighton. We walked just enough to see the lifesaving station having drills, the fort which once defended the Mersey and some of the honky-tonk businesses which appear at every seaside resort - we guess based on the principle that people who dare the beach will get hungry and want to repair to an arcade out of the cold! At the Floral Pavilion we shared tea and a scone in a quiet lobby cafe which was beginning to prepare for a wedding later in the day.

Port Sunlight

Port Sunlight Village is the name of the community built by Lever Brothers starting in 1888 to accommodate their plant work force; Sunlight was the name of the company's first soap product, to be followed by Lux, Lifebuoy and others.

William Lever grew rich, was a notable Freemason and owner of four large houses which he filled with art. Since he sometimes purchased entire collections of art, it might do to think of him as an art accumulator a la W. R. Hearst. In later life he built a large art gallery in Port Sunlight Village and arranged part of his art collection to fill the rooms which he then left to the public as the Lady Lever Art Gallery in honor of his wife. The gallery is strong in pre-Raphaelites, ceramics, and heavily decorated furniture.

Wedgwood, Lever Gallery

Wedgwood, Lever Gallery

There was a special exhibit of Rossetti paintings of Jane Morris, wife of William Morris, with whom Rossetti had a lengthy affair. The gallery also is known for one of the best collections of Wedgwood to be found anywhere.

Southport

Bob had mentioned a few days ago that it would be nice to see a model railroad museum. It promised to be sunny most of today, so we bought Range Rover tickets on the train, which would like us to ride all over the system in the general vicinity of Liverpool.

We asked if that meant Blackpool, and they said no, that really wasn't part of Merseyside -- it was all the way up in North Lancashire. To go to Blackpool would cost us almost four times as much as the Range Rover tickets, so we compromised and went to Southport.

Southport is, it seems to us, a perfectly splendid seaside resort for children and pensioners. Blackpool, we are told, is actually more of a swinging place for singles and childless couples.The train ride lasted about an hour, counting the change at Moorfields. Still we were early for England when we arrived a little before 10:00. We strolled down the streets, which were quite broad, admired the many Victorian buildings, and proceeded in the general direction of the shore.

We were looking to the right at a huge childrens' playground, and nearly walked by a high green fence on the left with a discreet sign reading "Model Railway Village." "I wonder when they open" was followed almost instantly by two large entrance gates opening up, so we were the first customers of the day.

Model Railway Village

This is a lovely garden, with a twisty macadam path which the visitor follows, looking at the detailed models of houses, boats, cars and -- yes, indeed! -- trains. We don't know exactly what gauge they were, but the rails were about three inches apart, the locomotives and cars about five inches wide and up to six inches high, just matching the scale of the buildings and vehicles and people.

Model Railway Village

This is a lovely garden, with a twisty macadam path which the visitor follows, looking at the detailed models of houses, boats, cars and -- yes, indeed! -- trains. We don't know exactly what gauge they were, but the rails were about three inches apart, the locomotives and cars about five inches wide and up to six inches high, just matching the scale of the buildings and vehicles and people.

As we watched, the village started up, with train after train being added to the track and following its circuit. There was a double track so there were three goods trains in one direction and two passenger trains in the other.The trains all had scheduled stops for signals, water refill, and passenger loading and unloading.

Little children were besides themselves with glee seeing these good sized trains (one engine looked just like Thomas) and had to be restrained from running up and touching them!

After the garden we passed by an old fashioned pitch and putt par-3 course. Southport is not far from the course used for the Ladies' British Open this year; golf is quite popular on the dunelands. Down the beach we saw a good-sized amusement park with some pretty good rides to excite teenagers.

Then we got on the oldest and second longest (at 1200+ yards) pier in England and walked to the end. The tide was going out, so the end of the pier was just beyond the water line. At high tide, on the other hand, the enormous beach would be covered by water. We had a lovely lunch and then continued riding the rails, slowly expanding our knowledge of Liverpool and environs. We declared the day a great success!

St. Helens

St. Helens is an industrial town about 12 miles west of Liverpool. For centuries there was no town at all but just farmland, but in the 18th century it became one of England's earliest coal mining areas. Soon glass production followed because

of the availability of sand, soda and lime in addition to coal, all in the same region. When James I banned the burning of timber because it was needed for shipbuilding, more industry moved to St.Helens to take advantage of the coal. Seeing the need to move heavy materials, the St. Helens industrialists created the Sankey Canal in 1757 to connect the coal mines to the Mersey River, then to Liverpool and eventually the rest of the world.

Art Glass, Pilkington's

Art Glass, Pilkington's

Pilkington Group Limited was founded in 1826 as St Helens Crown Glass Company. Crown glass was an early form of window glass, which was spun out by a glass blower to a diameter of 5 feet and then cut to size. Four sons of the Pilkington family developed the business vigorously throughout the Victorian era. The goal was to realize a continuous process for making sheet glass.

To this end, the company borrowed a furnace technique from the steel industry, reusing the extremely hot waste gases as part of the fuel mixture. The exhaust gas was alternately pumped to one side then the other through underground bricked passages where it cooled enough to be enriched with oxygen and blown across the fire. This yielded an 80% fuel saving.

Pilkington exchanged trade secrets with Henry Ford; Ford knew a lot about continuous processes (a.k.a. the assembly line) while Pilkington had great expertise in the manufacture of flat glass; their cooperation led to the use of glass windows in automobiles. But still the best flat glass had to be ground and then polished flat -- a terribly labor-intensive process. In 1905 a patent was issued for creating flat glass by floating the molten glass on a bed of molten tin, but not until 1953-7 did Sir Alastair Pilkington succeed in engineering this process to a commercially viable level.

The Float Glass Process was the biggest technological breakthrough for the glass industry since the Romans discovered glass blowing. All of the plate glass we take for granted in buses, trains, automobiles, and most important, skyscrapers, would be impossible without the float glass process.

And Pilkington, it turned out, was able to corner the market. By the beginning of 1992, Pilkington plc owned all but one of the manufacturing plants around the world employing the float process for making plate glass.

Our guide Tony Chisham, was the recently retired production manager of the large plate glass factory, now involved in guiding museum visitors. He had started right after high school in 1956, and kept getting promoted. He joked that he only worked on the "cold side" of the plant, where the plate glass was cut and packaged and shipped, and was never even allowed in the hot side, because the company guarded its secrets very closely. So when he was made plant manager he said, "how can I manage the plant when I've never been inside!"

He may have decided to take us in tow when we mentioned that glass was a liquid and flowed. Tony explained we were right and wrong, and pointed out that other substances, including pieces of amber millions of years old, do not flow. Glass is not crystallized, so technically a liquid, but still solid bound together chemically. The irregularities in older window glass were caused by the crown glass manufacturing process, and the practice by glaziers of setting the thicker edges at the bottom. He probably knew that we needed instruction.

Glass Workers' Friggers

Glass Workers' Friggers

True to his word, Tony led us around the museum, our own private tour guide, explaining the glass process from the Egyptians forward, until it was time for the glass blowing demonstration followed by the twenty-minute movie on Pilkington and the flat glass process, after which Tony picked us up again as we were proceeding over the bridge to the old 19th century Pilkington glass works, where he showed us the workings of the regenerative gas process for fuel efficiency. Considering that silica sand, soda, and lime, the raw materials needed for glass production, are so inexpensive, it was quite amazing that the plant was so elaborate and carefully engineered.

Wearing hard hats, we saw where water used to cool glass was dumped into the canal, yielding a popular swimming hole. Once a local pet dealer went bankrupt and gave away the remaining cats and dogs, but ended up dumping his whole stock of tropical fish in "The Hotties," where they flourished and became part of home fish tanks for many St. Helens boys. The tall smokestacks in the distance attest to the continued presence of Pilkington in the town, although now the payroll is in the hundreds where once it had been thousands.

At the end of the day glass blowers had to bank their ovens and there were always little bits of glass left over, which they were encouraged to play with to make little decorative objects, called "friggers," which were quite popular in Victorian times. The museum display of friggers included "walking sticks" which were hung on the wall in a worker's home; during the epidemics of the 19th and early 20th centure, these objects were thought to attract disease and were carefully cleaned daily. One particularly elaborate frigger is the carnival wheel.

Industrial glass making was always a physically hard job; the process involved dangerous gases, swinging the glass blowing rods often led to arthritis, and a major cause of injuries was cuts from cooled glass in the warehouse. Also, he pointed out that Victorian glassblowers had bad teeth, because the Victorians did not want the impurities in glass which gave it a bluish-green cast, so quantities of arsenic were added to the mixture to clarify the glass, inadvertently damaging the workers' teeth.

Some four hours after our arrival, we took notes on everything Tony Chisham had taught us over a late lunch of fish and chips, and have a new appreciation for the industrial might of England. And once again we learned that the best part of being a tourist is meeting interesting people.

Anderton

We set off to view the Anderton Boat Lift, another part of the canals and waterways historic trust. We'd seen something similar in Canada, but each boat lift is designed and built a little differently.

But first we had to take two train rides and a bus ride to get to the Boat Lift using public transportation from our flat in Birkenhead. We arrived shortly before 1100, having noted that there was a bus back at 1506, but after that not another bus until 1815. So we asked what we could do in the available time, and found out to our surprise that we could take a ride in a canal boat on the Weaver River, and then continue to ride up on the boat lift and still have time to catch our bus back to Liverpool.

Peregrine Falcon

Peregrine Falcon

After getting our tickets in order, the clerk told us where we would find exhibits and then, looking out the interview at a small clutch of people, said there was a special demonstration of birds of prey. We wasted no time getting out to see the birds!

There were owls of all sorts and a lovely young male peregrine falcon. The large eagle owl was 27 years old, a beautiful specimen. The barn owl was beautiful with tints of lilac among the white feathers.The exhibitors told us all about handling the birds, and offered people a chance to put on the glove and hold the bird, a little owl.

Surprising herself and Bob, Elsa volunteered.

Elsa Holds the Owl

Elsa Holds the Owl

Then it was time for our boat ride. We learned that this part of England was for millenia a major salt producer, as there were huge salt beds which are melted into brine and distilled into table salt. Also there is plenty of soda and limestone needed for the nearby glass industry, not to mention coal which must be barged in to distill the salt. So canals and improvements began in the 18th century, even predating the industrial revolution, which 'officially' begins with steam engines.

The canals operated with locks, but the 45 foot lift required a sequence of tedious locks and also used a lot of canal water. (Canal traffic was so heavy that preserving the water in the canals was a major economic factor.)

So in the 19th century money was raised to build a hydraulic lock which would take two immensely heavy cannisters, at least one of which contained a boat, of precisely equal weight and therefore in balance. Water was pumped out of one cannister until the other started to descend, reversing the position of the two cannisters. No engines were required, just a large hydraulic lift.The lift was made of iron, which was slowly corroded by the natural salt.

Anderton Boat Lift

Anderton Boat Lift

The canal system fell into disuse towards the end of the twentieth century, and with the aid of English Heritage, the British government, and a lot of enthusiastic volunteers, funds were raised and the canal system is now restored into large scale recreational use. Many of the staff at the lift are volunteers.

For 7 milion pounds, a goodly portion from the national lottery, the Anderton Boat Lift was completely re-engineered with a modern computer-operated hydraulic lift. Perhaps the most impressive part of the overall system is that it takes just minutes for one boat to go up while the other comes down.