We have been traveling in the Eastern mountains, as they gradually emerge in autumn color. We're delighted to drive along roads that are new to us, twisting from one country farm to another, past fields of corn and beans ready for harvest  Steam locomotive control panel

and apples falling from orchard trees. Many places in the country are well and fully decorated for harvest and Halloween. We are spending a few nights in State College, Pennsylvania, a pleasant city surrounded by farmland, rivers, spiky mountains and small towns.

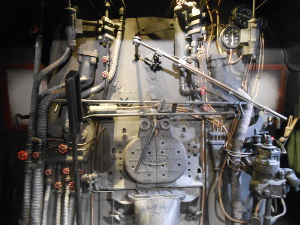

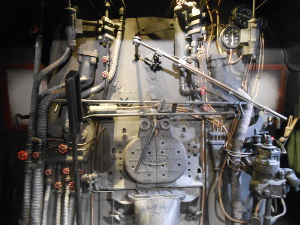

Steam locomotive control panel

and apples falling from orchard trees. Many places in the country are well and fully decorated for harvest and Halloween. We are spending a few nights in State College, Pennsylvania, a pleasant city surrounded by farmland, rivers, spiky mountains and small towns.

In Altoona, Pennsylvania, we visited the Railroaders Museum, a relatively new and quite attractive museum celebrating the rise and fall of railroading in Pennsylvania. They offer a two-part visit: first we toured the museum, then we drove a half-dozen miles out of town to the Horseshoe Curve. Both gave us plenty to think about.

In 1854 the Pennsylvania Railroad ("Pennsy") was racing to compete with the Chesepeake and Ohio Railroad to complete track to Pittsburgh. They came flat up against a hill which was too steep to climb, at least for the steam engines of the day. An engineer hit upon the solution of climbing the hill more gradually by building a giant horseshoe curve for the sole purpose of slowly gaining altitude.

A few hundred Irishmen were hired, given picks, shovels, black powder and  Neighborhood bar exhibit

not much else, and told to build the curve. It involved filling in a pretty good size gap, while still allowing for drainage, and laying track along the way.

Neighborhood bar exhibit

not much else, and told to build the curve. It involved filling in a pretty good size gap, while still allowing for drainage, and laying track along the way.

It worked, and it was the engineering marvel of the day. The Pennsy won the race and began a long period of substantial growth and prosperity. By 1904 an average of 168 trains a day transited the Horseshoe Curve. Passenger train conductors announced the curve and heads were poked out windows to appreciate the view.

The Pennsy valued engineering and promoted from within, so its presidents all had operating or engineering backgrounds. It insisted on building its own locomotives and rail cars, as well as laying and maintaining its own track. And since the heart of the Pennsy was keeping the Horseshoe Curve in steady  Looking up at the Curve

operation, it quickly built its manufacturing, operating, maintenance, research, test, and development center in nearby Altoona.

Looking up at the Curve

operation, it quickly built its manufacturing, operating, maintenance, research, test, and development center in nearby Altoona.

Altoona has always been a railroad town, and in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries almost exclusively a railroad town. The population was once nearly 90,000 (it's about half that now), and the Pennsy ran the show. It was good work, it paid well, especially if you could land a more highly skilled or managerial job, and it was steady work for generations of railroad workers.

The Pennsy early on decided to exploit the coal fields of western Pennsylvania, which supplied the power to run hundreds of fine steam locomotives. Even when other railroads were switching to oil-fueled diesel electrics, the Pennsy stayed faithful to steam. This merely made the fall more precipitous for the city of Altoona when the Pennsy switched to diesels. Thousands of workers were laid  Modern track maintenance

off, and what had been a wondrous story of railroad prosperity suddenly shifted to a dismal saga of unemployment and despair. The trains that run daily over the Horseshoe Curve don't stop in Altoona the way they used to.

Modern track maintenance

off, and what had been a wondrous story of railroad prosperity suddenly shifted to a dismal saga of unemployment and despair. The trains that run daily over the Horseshoe Curve don't stop in Altoona the way they used to.

The museum spent a lot of time explaining how the Altoona railroaders felt about their jobs and their company. One great exhibit showed the working side (the interior) of a steam locomotive, where the engineer had to sit and operate the train. Another exhibit depicted a typical Altoona bar, with two flat screen TVs where the mirrors would be behind the bar, so the visitor could climb on a bar stool and watch a video presentation of the attitudes of working class workers who went to the bar. There was plenty of employment discrimination a century ago.

The world famous Horseshoe Curve also turned out to be a special treat. One railroad buff sent his drone up in the sky to photograph and observe the trains and maintenance crews. The rest of us were, generally, railroad fans, perhaps including some retired railroaders.

Parking at the base of the hill, we rode an "inclined plane" up to the level of the track just at the horseshoe bend. The day we visited, the railroad crews  Work stops for a passing train

were working on maintaining the curved track. Loudspeakers broadcast the talk between the workers, which seemed to be mostly positioning information Because it is such a sharp curve, the track requires frequent maintenance to keep the exact distance between the rails and prevent bumps as the trains round the corner, their wheels shrieking with the friction of the curve. The orange colored machines (there were at least a dozen of different designs and uses) automatically fastened the rails to new ties that had recently been installed. We had already learned of the critical importance of maintaining the track, and now, watching the intense attention paid by the workers, we were convinced.

Work stops for a passing train

were working on maintaining the curved track. Loudspeakers broadcast the talk between the workers, which seemed to be mostly positioning information Because it is such a sharp curve, the track requires frequent maintenance to keep the exact distance between the rails and prevent bumps as the trains round the corner, their wheels shrieking with the friction of the curve. The orange colored machines (there were at least a dozen of different designs and uses) automatically fastened the rails to new ties that had recently been installed. We had already learned of the critical importance of maintaining the track, and now, watching the intense attention paid by the workers, we were convinced.

They stopped as a freight train came down the hill and slowly passed them, then continued down the eastern side of the curve in the general direction of Philadelphia -- or who knows where?

There are still over 50 trains a day using the Horseshoe Curve, and it's still an engineering marvel. No better way for trains to get to Pittsburgh from the East has ever been created.

Steam locomotive control panel

and apples falling from orchard trees. Many places in the country are well and fully decorated for harvest and Halloween. We are spending a few nights in State College, Pennsylvania, a pleasant city surrounded by farmland, rivers, spiky mountains and small towns.

Steam locomotive control panel

and apples falling from orchard trees. Many places in the country are well and fully decorated for harvest and Halloween. We are spending a few nights in State College, Pennsylvania, a pleasant city surrounded by farmland, rivers, spiky mountains and small towns.

Neighborhood bar exhibit

Neighborhood bar exhibit Looking up at the Curve

Looking up at the Curve Modern track maintenance

Modern track maintenance Work stops for a passing train

Work stops for a passing train